The lead up to competition can be a stressful time, and often that stress can hinder your chances of a successful performance. There are various inputs to your performance, and in this article we will be looking at your physical training (Strength & Conditioning), fuelling and recovery (Nutrition), and your mindset & focus (Psychology), and how to use them to your advantage to prepare for competition.

Strength & Conditioning

Strength & Conditioning (S&C) is used to improve an array of physical qualities such as speed, agility, strength, and power, among others. Any kind of training you do, be it S&C, tactical training, or skills training, will induce a level of fatigue proportionate to the work performed. Acute fatigue can build very quickly, even after one repetition of an exercise (1), and systemic fatigue accrued from many subsequent training sessions can take days to weeks to dissipate (2). Physical Adaptations, on the other hand, take weeks to months to fully occur (3). Luckily, fatigue can dissipate much more quickly (2), and physical adaptations can be maintained for much longer, even with infrequent training (4). While S&C training is vital to improve your physical qualities (link here), training volume and intensity should be tapered down as you get closer to competition to ensure you’re competing with as little fatigue as possible.

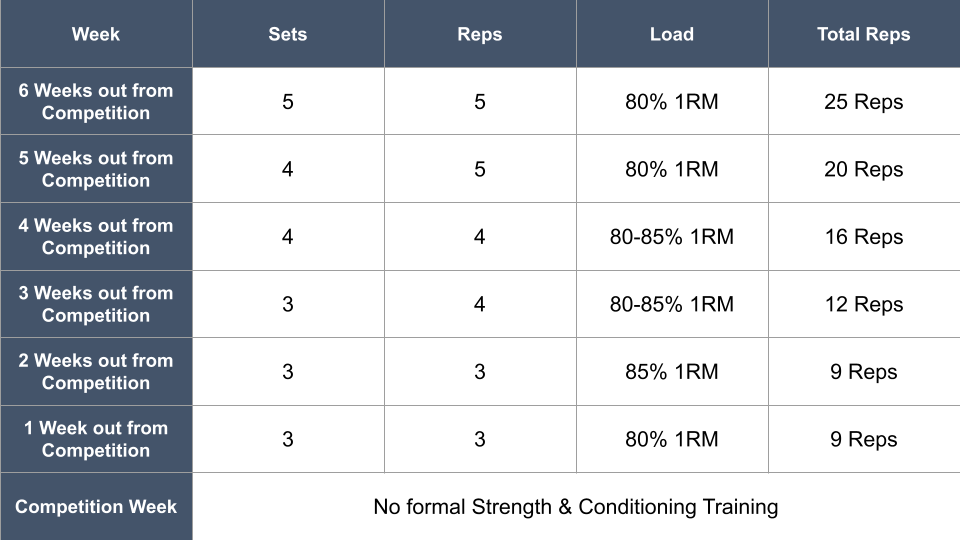

As you approach any competition, the volume of your training, including skills and tactics training, should decrease to ensure freshness. Initially, however, the intensity should be kept high to ensure improvements are made in your performance, and to simulate competition conditions. The same is true for S&C training – reductions in training volume (number of sets and reps) will facilitate fatigue dissipation, whereas intensity should be kept quite high to ensure no losses in strength. Further, it is advised to stay away from training to failure, as that kind of training builds more fatigue, and doesn’t seem to improve strength compared to staying a few reps shy of failing (2, 5). This will also maintain good speed of movement, and proper technique.

In the final 1-2 weeks of training before a competition, both Volume and Intensity should drop considerably compared to training in the off-season, weeks or months away from competition. This is to absolutely ensure that there is as little fatigue building as possible, and as there are little to no physical adaptations that can take place in such a short timeframe, there is no serious downside to reducing your S&C training considerably for a 1–2-week period before a competition. A sample training block may look like this:

Nutrition

As discussed above, in the lead up to competition, training will often be intense and high in volume. What you eat throughout this period can impact the success of your training and subsequent taper, especially from a recovery, immunity, and body composition perspective.

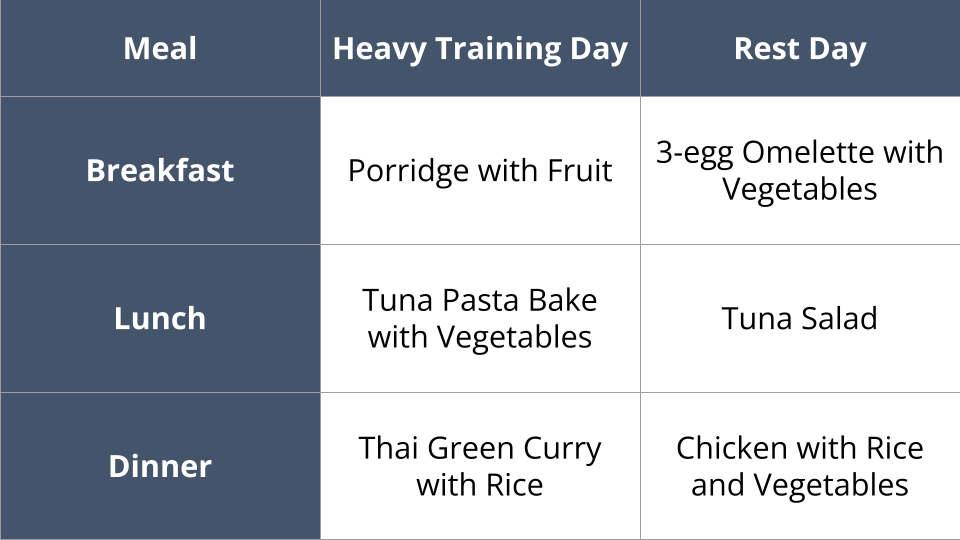

Compared to a normal training week, the week leading up to competition should be lower in both training intensity and volume. A useful phrase to keep in mind is “fuel for the work required”, which involves manipulating daily carbohydrate intake depending on the intensity and duration of a training session. Periodising your carbohydrate intake will ensure that you are fuelling and recovering well from training as well as managing body composition. In practice, on heavier training days carbohydrate should be consumed as part of pre- and post-training meals as well as part of snacks throughout the day. However, on light training days or rest days, less carbohydrate and more protein may be consumed in order to match energy requirements and promote satiety.

Below is an example of how to periodise carbohydrate intake:

Training leading up to competition can often be intense, and your nutrition should also play a key role in recovery by helping to replenish energy stores and reduce muscle fatigue. Throughout the taper, keep in mind the “Three R’s of Recovery”: refuel, repair and rehydrate. Post-training meals should contain a portion of complex carbohydrates to replenish glycogen stores, as well as a lean source of protein (~20-40g of protein) to support muscle repair. Great examples include spaghetti bolognese, salmon with sweet potato and vegetables, and scrambled eggs on toast. Ideally, these should be consumed within 2-3 hours of finishing training.

In addition, try to consume antioxidant rich food throughout a taper week. Consuming foods such as berries and beetroot as well as some spices (e.g., turmeric and ginger) and nuts (e.g., walnuts and pecans) could help reduce muscle damage, fatigue, and any unnecessary inflammation.

Aim to have at least five portions of fruit and vegetables per day. This can easily be achieved by including at least two or three different vegetables at each meal as well as one portion of fruit as a snack. Omega-3 fatty acids, which are most abundant in oily fish, can also have a positive effect on the immune system. Aim to consume at least one portion of oily fish such as salmon or mackerel at least once per week. Plant-based omega-3 sources include chia seeds, flax seeds, and walnuts.

Psychology

Competition day can be a stressful event, and oftentimes that stress can hinder an athlete’s chances of a successful performance. By implementing some simple mental preparation strategies into your regular preparatory routine – alongside logistical preparation, nutrition and hydration, and physical activation – athletes can maximise their potential for success during competition.

A pre-performance routine can be described as a “sequence of task relevant thoughts and actions an athlete engages in prior to performing”. Pre-performance routines can be distinguished from superstitious behaviours, which are often irrational and compulsive actions that are not relevant to the task at hand. Pre-performance routines, on the other hand, are functional as they direct your thought processes and emotions to help to reduce anxiety (7), improve focus (8) and reach optimal arousal level (9).

In general, the most common mental elements of a pre-performance routine include, but are not limited to, imagery, self-talk, relaxation, and external focus of attention (10). Imagery refers to the mental creation and re-creation of an experience, such as overcoming a difficult situation or imagining the rehearsal of a specific sport skill. Self-talk describes the internal chatter that reverberates in our heads. Athletes can leverage the use of self-instructional strategies such as cue words and mantras to boost confidence, improve motivation and skill execution. Relaxation elements typically involve deep breathing exercises aimed at controlling heart rate and other physiological markers. Finally, external focus of attention is usually prompted by concentrating on a task-relevant cue in the performance environment (i.e. a target) (9,11,12).

Due to its proven effectiveness and popularity, imagery should form a key component of a pre-performance routine. This mental skill is something that many athletes already inadvertently practice when they daydream about their desired performance in competitions. Doing this systematically, however, using a structured and detailed approach can be a beneficial strategy in the lead up to competition for any athlete, regardless of sport and level. It is well known that effective use of imagery can influence performance in many ways by increasing confidence, regulating anxiety, enhancing motivation and much more (10,15,16).

Creating your own imagery script

To use imagery effectively it is recommended that you create a script to ensure that the images and feelings created are vivid and realistic. Firstly, you should determine what type of imagery you want to engage in prior to a competition, as choosing the relevant area of focus in relation to your goal will increase chances of success (8):

1. Mentally rehearse race plans, strategies, and routines. This would provide general performance benefits.

2. Mentally rehearse specific sport skills so you enhance the execution of skills you already know and/or are learning.

3. To improve feelings of relaxation, stress, anxiety, emotions and arousal. This is often used to decrease anxiety or ‘psych up’ prior to a competition.

4. To help you feel in control, focused, mentally prepared and confident.

5. To allow you to imagine goal achievement and accomplishments like winning.

To create a personalised and meaningful script, you need to consider (13,14) :

1. What is the purpose? To improve a skill or to motivate yourself? The selected focus from the five imagery types will determine the content of their script.

2. Where and when will you listen to the recording? During training, relaxing in bed, pre-competition?

3. Which senses can you include? Sight, sound, taste, touch or smell? To ensure your practice is as realistic as possible, the script needs to incorporate as many senses as you are comfortable in imagining.

4. Who will record it? Yourself or something else? The voice, tonality, tempo and pronunciations should serve to support the athlete’s concentration rather than distract him/her from the experience. If the sport you compete in includes background music, this should also be incorporated into the recording.

5. Keeping it short. The script should initially be no longer than 2-3 minutes. As you develop your imagery ability, the length can be gradually increased and incorporate more senses.

6. Once the script is written and recorded, you should aim to integrate regular imagery session into your performance routine. Imagery practice is just as important as physical practice.

7. Finally, you should frequently evaluate and consider how the script can be updated to ensure it remains relevant and effective.

The lead-up to competition is the most vital part of the season, and there are many factors at play to determine whether you perform your best. At Innervate Performance we will remove the guesswork and ensure that your preparation is as good as it can be, so that you can focus on performing when it matters the most. Get in touch to find out more at info@innervateperformance.com

References

García-Ramos A, Padial P, Haff GG, Argüelles-Cienfuegos J, García-Ramos M, Conde-Pipó J, Feriche B. Effect of Different Interrepetition Rest Periods on Barbell Velocity Loss During the Ballistic Bench Press Exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2015 Sep;29(9):2388-96. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000891. PMID: 26308827.

Morán-Navarro R, Pérez CE, Mora-Rodríguez R, de la Cruz-Sánchez E, González-Badillo JJ, Sánchez-Medina L, Pallarés JG. Time course of recovery following resistance training leading or not to failure. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017 Dec;117(12):2387-2399. doi: 10.1007/s00421-017-3725-7. Epub 2017 Sep 30. PMID: 28965198.

Stock MS, Mota JA, DeFranco RN, Grue KA, Jacobo AU, Chung E, Moon JR, DeFreitas JM, Beck TW. The time course of short-term hypertrophy in the absence of eccentric muscle damage. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017 May;117(5):989-1004. doi: 10.1007/s00421-017-3587-z. Epub 2017 Mar 20. PMID: 28321637.

Hwang, Paul S.1; Andre, Thomas L.1; McKinley-Barnard, Sarah K.2; Morales Marroquín, Flor E.1; Gann, Joshua J.1; Song, Joon J.3; Willoughby, Darryn S.1 Resistance Training–Induced Elevations in Muscular Strength in Trained Men Are Maintained After 2 Weeks of Detraining and Not Differentially Affected by Whey Protein Supplementation, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: April 2017 - Volume 31 - Issue 4 - p 869-881

Santanielo N, Nóbrega SR, Scarpelli MC, et al. Effect of resistance training to muscle failure vs non-failure on strength, hypertrophy and muscle architecture in trained individuals. Biology of Sport. 2020;37(4):333-341. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2020.96317.

Moran, A. P. (1996). The psychology of concentration in sports performers: A cognitive analysis. Hove, UK: Psychology Press

Hazell, J., Cotterill, S. T., & Hill, D. M. (2014). An exploration of pre-performance routines, self- efficacy, anxiety and performance in semi-professional soccer. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(6), 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.888484

Shaw, D. (2002). Confidence and the pre-shot routine in golf: A case study. In I. Cockerill (Ed.), Solutions in sport psychology (pp.108–119).

Mesagno, C., & Mullane-Grant, T. (2010). A comparison of different pre-performance routines as possible choking interventions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(3), 343–360. https://doi. org/10.1080/10413200.2010.491780

Anton G. O. Rupprecht, Ulrich S. Tran & Peter Gröpel (2021): The effectiveness of pre-performance routines in sports: a meta-analysis, International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, DOI: 10.1080/1750984X.2021.1944271

Wadey, Ross & Hanton, Sheldon. (2008). Basic Psychological Skills Usage and Competitive Anxiety Responses: Perceived Underlying Mechanisms. Research quarterly for exercise and sport. 79. 363-73. 10.5641/193250308X13086832906030.

Hardy, L., Jones, J. G., & Gould, D. (1996). Understanding psychological preparation for sport: Theory and practice of elite performers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Perry, J. (2019). Performing Under Pressure: Psychological Strategies for Sporting Success (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429319150

Orlick, T. (2007). In pursuit of excellence (4th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Garza, D. L., & Feltz, D. L. (1998). Effects of Selected Mental Practice on Performance, Self-Efficacy, and Competition Confidence of Figure Skaters, The Sport Psychologist, 12(1), 1-15.

White, A., & Hardy, L. (1998). An in-depth analysis of the uses of imagery by high-level slalom canoeists and artistic gymnasts. The Sport Psychologist, 12(4), 387–403.

Le Meur, Y. Hausswirth, C. & Mujika, L. (2012). Tapering for competition: A review. Science & Sports. 27, pp.77-87.

Mujika, I., Padilla, S., Payne, D. & Busso, T. Physiological changes associated with the pre-event taper in athletes. Sports Medicine. 34, pp. 891-927.

Mujika, I. (2011). Tapering for triathlon competition. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise. 6(2),

pp.264-270.

Trent, S. Maughan, R. & Burke, L. (2011). Nutrition for power sports: middle-distance running, track

cycling, rowing, canoeing/kayaking, and swimming. Journal of Sport Sciences. Pp. 1-11.

Will has a Master’s degree in Strength & Conditioning from Middlesex University, and is a published scientific author. Will has worked with athletes across a variety of sports including rugby, football, hockey, cycling, rowing, and recently was the Head of Strength & Conditioning for the inaugural year of the NFL Academy in North London. For more information about Innervate Performance, check out our coaches page

Harriet is a Performance Nutritionist at Loughborough University where she specialises in supporting team-based university, national and international athletes. Harriet has worked within a multitude of sport including hockey, basketball, badminton and cricket. Harriet is a graduate in Sport and Exercise Science (2014) from the University of Leeds and also has a master in Sport and Exercise Nutrition (2016) from Loughborough University

Tulio is a Performance Psychology Consultant at University College London (UCL), and is a UK Representative of the European Network of Young Specialists in Sport Psychology (ENYSSP). He holds a BSc in Sport and Exercise Sciences (Human Performance), and an MSc Sport and Exercise Psychology. Tulio is also a Supervised Sport Scientist (Psychology) with the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences (BASES)