Strength & Conditioning

When it comes to physical preparation, every sport is going to require a different athletic profile. Training for a rower, footballer or sprinter will all be different, and will even depend on what position or role you perform in your sport. However, there are a few physical qualities that essentially every athlete needs and will benefit from developing: Strength, Power, Rate of Force Development (RFD), and Endurance, though the exact magnitude to which each of those properties will need to be developed will vary quite widely. To perform at your physical best on game day, you will need to have trained each of those qualities to their fullest possible extent given the time you have available to you in training.

While you’re further away from competition, your S&C training will likely be more focused towards less specific elements of the sport such as Work Capacity, Hypertrophy and Strength. Strength has been shown to have a direct correlation to more specific performance metrics like Power (1), Hypertrophy is a key driver for force production in trained athletes (2), and as training volume is highly correlated with Hypertrophy (3), developing the work capacity to perform enough volume is key to laying the foundation for a stronger, more powerful body. We’ve written about why strength is so important for athletes and the best exercises to build strength, and while these should be staples of any S&C routine, a general training programme can and should consist of much more exercise variety to more fully develop your muscles (4), sets and reps should be higher to promote hypertrophy, and rest times should be kept shorter to improve work capacity and general conditioning.

As you get closer to competition, your sport training will likely increase in intensity, and take up more time between longer and/or more frequent sports training. As such, your S&C training will have to decrease in volume, and become more specific to the adaptations that you need for your sport. A programme focused on Maximal Strength, Power and RFD will be best placed to allow you to perform at your best in competition, and these programmes tend to be much lower in volume, higher in load, and afford you more rest between sets and sessions. Max Strength can be elicited with twice-weekly training, loads at or above 85% of 1RM, and with roughly 8 sets per week (5). We’ve written before about how to maximise power and RFD for sport, so be sure to read that for a full explanation, but in summary, Power/RFD training should be low in volume, consist of less than 6 reps per set, and the load should be lower to allow for high movement velocities with as little deceleration as possible. As you approach competition day, your training should decrease in volume and intensity to allow fatigue to dissipate. This is a standard practice to perform a peak (read more about that here). Ideally, you will have trained correctly in the lead up to gameday to have developed your strength, power, and endurance, and a short taper will allow you to fully express those physical qualities in competition.

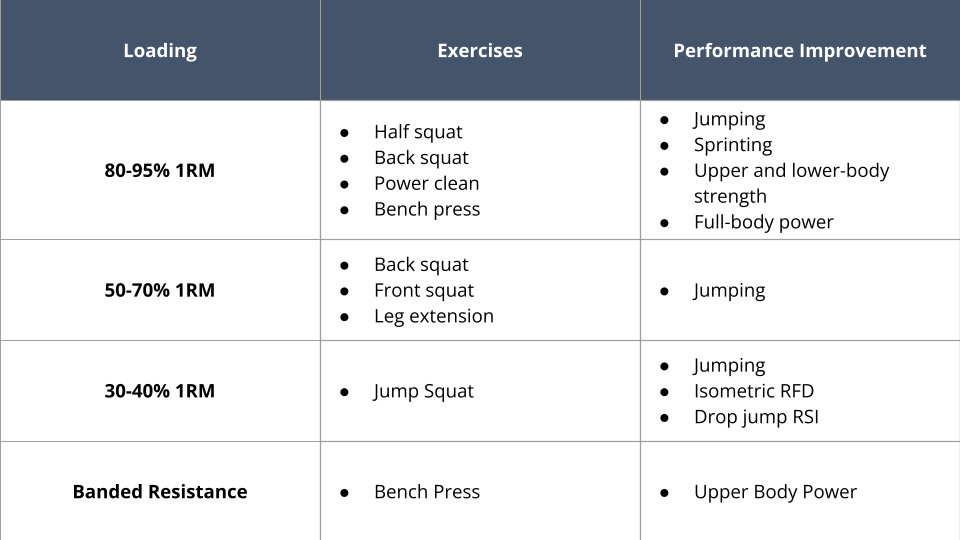

In the days leading up to competition, some priming can be completed to improve athletic performance. What this means is that performing some relatively low-volume resistance training the day before or the morning of competition can help with your performance on the pitch. An analysis of the effective exercises, loading ranges and times was performed by Harrison et al. in 2019 (12), a summary of which you can see below:

Although this priming can improve performance, care must be taken not to induce fatigue with these exercises and parameters. A practical way to implement these might look like this:

Day Before Competition

1) Jump Squat 2 x 3 @30% 1RM

2) Back Squat 3 x 3 @80% 1RM

C1) Bench Press 3 x 4 @80% 1RM

Morning of the Competition at least 6 hours prior to your event

1) Jump Squat 2 x 3 @30% 1RM

2) Power Clean 3 x 3 @80% 1RM

Immediately prior to competition, you need to perform an appropriate warm-up to maximise performance and reduce the risk of injury. Your warm-up should follow the RAMP protocol as below:

Raise: this part of the warm-up should raise your pulse, body temperature, and get you feeling warmer and looser, especially if you’ve been sitting down to travel, or if it’s early in the morning

Activate: here, we want to activate and engage the relevant muscles and movements that will be involved in your event.

Mobilise: we’ll need to mobilise any joint that can be moved through substantial ranges, or if there are any joints or muscles that can flare up or give you pain during an event, this is the time to stretch them out, or loosen up a joint

Potentiate: in this final part of a warm-up, we will be performing actions very similar to what you’ll be doing in the competition itself, which will vary from sport to sport

Some of the categories of warm-ups may blend into each other, as you’ll see in this example of what an effective warm-up might look like before a football match:

Short, slow-paced 2-3 minute jog around the pitch (Raise)

Lunge with Twist x 8 per side (Raise, Activate & Mobilise)

Leg Swings x 8 per direction (Raise, Activate & Mobilise)

High Kicks x 8 per side (Raise, Activate & Mobilise)

Butt Kicks x 15 per side (Raise, Activate, Mobilise & Potentiate)

High Knees x 15 per side (Raise, Activate, Mobilise & Potentiate)

Lateral Lunges with High Knee (Activate, Mobilise & Potentiate)

Pogos x 10 (Potentiate)

Side Shuffle x 15 seconds per side (Potentiate)

20m sprints @ 50%, 75%, 90% effort (Potentiate)

NUTRITION

We’ve written before about how to eat in the lead-up to competition, and many of the same practices and concepts apply here. Similar to Strength & Conditioning, a huge determinant of how well you perform on gameday will be how well you’ve used nutrition to recover from training, and fuel yourself to do your best in training sessions.

When it comes to competition, What you eat in the hours leading up to a game can positively impact your energy levels and ability to concentrate. This article will discuss the importance of pre-game fuelling and hydration as well as share some tips on how to turn up to a game ready-and-raring to go.

Pre-Game Meals

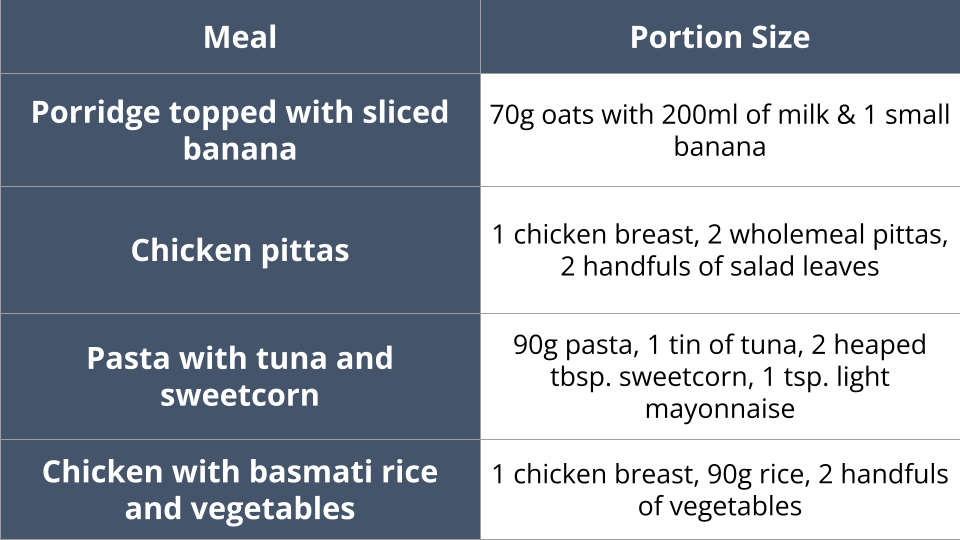

The 3-4 hours leading up to a game are a prime opportunity to fuel appropriately. Depending on the nature of your sport, look to consume between 1-4g of carbohydrate per kilogram of body mass (i.e. 1-4g/kg) within this time frame. For example, this would equate to 70-280g carbohydrate for a 70kg athlete. Some people may wish to consume this as part of a pre-game meal alone, whereas others may wish to have a pre-game snack as well.

Not all carbohydrates are the same. Pre-game meals should comprise lower glycaemic index (GI) carbohydrate. Low GI carbohydrates provide energy over a longer period of time and can be found in foods such as pasta (cooked al dente), basmati rice, sweet potato and porridge oats.

In addition, try to avoid high-fat foods such as heavy creams, cheese and fatty-meats prior to a game. These foods can take longer to digest and could therefore cause stomach discomfort during a game.

Pre-Game Snacks

Pre-game snacks should comprise of higher glycaemic index carbohydrate to give you a quick burst of energy. These should be consumed ~60-90min prior to the game, which for some may be just before warmup. Great pre-game snacks include the likes of banana, rice cakes and Soreen.

Hydration

Hydration plays an important role in many physiological processes, one being concentration. Your ability to concentrate, read the game and listen to your coach and teammates is critical when it comes to game-day success. In the lead up to a game, try to have at least a pint of water when you wake up and again alongside your pre-game meal. Always carry a water bottle with you to sip on until the start of the game.

Half-Time Strategies

Carbohydrate is stored in the muscles and liver as glycogen; these can be considered as the battery stores in your body. Throughout a game or competition these battery stores start to deplete. Therefore, half-time is the perfect opportunity to re-charge these batteries. Here, food such as jelly babies, flapjack or a sports drink, which all contain high GI carbohydrates, can act as the perfect snack.

It is important to remember that there is no “one size fits all” approach when it comes to game-day nutrition. Training is a perfect opportunity to practice fuelling and half-time strategies. As an example, in the lead up to training you can trial different meals and snacks as well as experiment with when you eat these. Once you feel confident in what you’re eating before training, this can then start to form part of your pre-game nutrition strategy.

PSYCHOLOGY

When you want to perform at your best, the last thing you need is stress getting in the way on gameday. Stress is an intriguing phenomenon – our stress response (often called the “fight, flight or freeze” response (13) is designed to prepare us for physical activity. This response increases our heart rate, breathing, and blood flow to the muscles in our arms and legs. In the right dose, stress can be very helpful for sporting performances. However, the wrong stress levels can lead to underperformances – sometimes catastrophic ones. So, being able to manage your stress levels to find the right balance is vital to performance. Stress levels can fluctuate between being too low or too high. The amount of stress that works best for someone is known as their optimal arousal level (14). Optimal arousal levels differ (sometimes dramatically) from one person to another (15) and naturally rise and fall over time. Therefore, it is important to reach – and maintain – your optimal level when you need it most. The first step in identifying your optimal arousal level is reflecting on your past performances (both good and bad). The aim is to understand:

How you felt before and during a competition and

Whether it was helpful to your performance. Were you calm, excited, nervous, or energetic? Were you confident or doubtful?

The answers will help you get a sense of your optimal arousal level. Next, you want to uncover the factors that created this emotional and psychological state. What did you do (or not do) that made you feel that way? The key here is to honestly evaluate what works for you (rather than what you think should work). The next step is creating your own pre-performance routine that incorporates the helpful elements – this can start hours, or even days, before the competition. This routine should include all your usual pre-competition prep, like warming up, hydrating and fuelling, and changing into your kit. Your routine can also include specific tools to manage arousal levels. To reduce arousal levels, you can use relaxation techniques (16). There are various techniques to choose from and online resources to coach you through them – my personal favourites are diaphragmatic breathing and progressive muscle relaxation.

Laughter can also be a helpful way to lower stress levels (17). Perhaps think of a teammate you can share jokes with or have a funny YouTube channel or podcast available. To increase arousal levels, you can trick your brain by physically doing what it would do when it is stressed; you can breathe faster and shallower (18) and do explosive exercises to increase your heart rate (19).

Finally, some tools are effective for increasing and reducing arousal levels. Music is one example, so you may want to create separate playlists to do each (20,21) . Another is imagery (commonly called visualisation), which involves creating scenarios that excite, calm, or build confidence (22) . One key point is that a routine differs from superstition. A routine is built out of components directly within your control, while a superstition relies on luck or coincidence (23) . It is also important that the routine is not too rigid – there should be enough flexibility to deal with unexpected events and delays. As such, it can be helpful to think of the routine as a sequence of processes (e.g., I do this after that) rather than a strict timetable (e.g., I do this exactly 30-minutes before the start) (24) .

In our article on Peaking for Competition, we go into great detail about creating an imagery script to harness the power of your psychology to maximise your performance on the day. This imagery script is best performed by the athlete immediately before competition to maximise its effect by reducing anxiety, improving focus and reaching optimal arousal level (6,7,8). Imagery should form a key part of every athlete’s pre-competition routine, and can be performed and adjusted regularly in the lead-up to game day.

For a full write-up on how to create your own imagery script, we recommend you check out our guide on How to Peak for Competition, and here are some key points on how to implement it when complete:

1. Is the intended purpose of the script to improve a skill or to motivate yourself?

2. Where and when will you be able to listen to the recording before competition?

3. Which senses can you include? Sight, sound, taste, touch or smell? To ensure your imagery is as realistic as possible, the script needs to incorporate as many senses as you are comfortable in imagining.

4. Who will record it? Yourself or something else? The voice, tonality, tempo and pronunciations should serve to support your concentration rather than distract you from the experience. If the sport you compete in includes background music, this could also be incorporated into the recording.

5. Keep it short. The script should initially be no longer than 2-3 minutes. As you develop your imagery ability, the length can be gradually increased and incorporate more senses.

To perform your best on gameday, the most important factor is to ensure you have adequately prepared for the weeks and months leading up to the competition. There is nothing you can do on the day itself to make up for poor tactical or physical training, and inadequate preparation. Proper psychological and nutritional regimens on the day of competition will allow you to fully express the months of training you have done to give you the best chance of success. At Innervate Performance, we can give you the best chance of performing at your best when it matters the most by setting you up for success. Get in touch to find out more at info@innervateperformance.com

Reference

Peterson MD, Alvar BA, Rhea MR. The contribution of maximal force production to explosive movement among young collegiate athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2006 Nov;20(4):867-73. doi: 10.1519/R-18695.1. PMID: 17194245.

Balshaw TG, Massey GJ, Maden-Wilkinson TM, Lanza MB, Folland JP. Neural adaptations after 4 years vs 12 weeks of resistance training vs untrained. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019 Mar;29(3):348-359. doi: 10.1111/sms.13331. Epub 2018 Dec 9. PMID: 30387185.

Brigatto FA, Lima LEM, Germano MD, Aoki MS, Braz TV, Lopes CR. High Resistance-Training Volume Enhances Muscle Thickness in Resistance-Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2022 Jan 1;36(1):22-30. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003413. PMID: 31868813.

Costa BDV, Kassiano W, Nunes JP, Kunevaliki G, Castro-E-Souza P, Rodacki A, Cyrino LT, Cyrino ES, Fortes LS. Does Performing Different Resistance Exercises for the Same Muscle Group Induce Non-homogeneous Hypertrophy? Int J Sports Med. 2021 Jul;42(9):803-811. doi: 10.1055/a-1308-3674. Epub 2021 Jan 13. PMID: 33440446.

Peterson MD, Rhea MR, Alvar BA. Applications of the dose-response for muscular strength development: a review of meta-analytic efficacy and reliability for designing training prescription. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 Nov;19(4):950-8. doi: 10.1519/R-16874.1. PMID: 16287373.

Hazell, J., Cotterill, S. T., & Hill, D. M. (2014). An exploration of pre-performance routines, self- efficacy, anxiety and performance in semi-professional soccer. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(6), 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.888484

Shaw, D. (2002). Confidence and the pre-shot routine in golf: A case study. In I. Cockerill (Ed.), Solutions in sport psychology (pp.108–119).

Mesagno, C., & Mullane-Grant, T. (2010). A comparison of different pre-performance routines as possible choking interventions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(3), 343–360. https://doi. org/10.1080/10413200.2010.491780

Clyde, W., & Serratosa L. 2006. Nutrition on match day. Journal of Sport Sciences. 24(7), pp.687-697.

Hills, S. &Russell, M. 2018. Carbohydrates for soccer: a focus on skilled actions and half-time practices. 10(1) 22.

Holway, F. & Spriet, L. 2011. Sport-specific nutrition: practical strategies for team sports. Journal of Sport Sciences. 29(1). Pp. 115-125.

Harrison PW, James LP, McGuigan MR, Jenkins DG, Kelly VG. Resistance Priming to Enhance Neuromuscular Performance in Sport: Evidence, Potential Mechanisms and Directions for Future Research. Sports Med. 2019 Oct;49(10):1499-1514. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01136-3. PMID: 31203499.

Roelofs, K. (2017). Freeze for action: neurobiological mechanisms in animal and human

freezing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1718),

20160206.

Wrisberg, C. A. (1994). The arousal–performance relationship. Quest, 46(1), 60-77.

Hanin, Y. L. (2010). Coping with anxiety in sport. Coping in sport: Theory, methods, and related

constructs, 159, 175.

Pineschi, G., & Di Pietro, A. (2013). Anxiety management through psychophysiological techniques:

Relaxation and psyching-up in sport. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 4(3), 181-190.

Akimbekov, N. S., & Razzaque, M. S. (2021). Laughter therapy: A humor-induced hormonal

intervention to reduce stress and anxiety. Current Research in Physiology, 4, 135-138.

Taylor, J., & Schneider, T. (2005). The triathlete’s guide to mental training. Boulder, CO: VeloPress.

Le Deuff, H. (2002). Entraınement mental du sportif: Comment eliminer les freins psychologiques

pour atteindre les conditions optimales de performance [Mental training for athletes: How to eliminate

psychological barriers to achieve optimal performance conditions]. Paris, France: Editions Amphora.

Karageorghis, C. I. (2008). The scientific application of music in sport and exercise. Sport and

exercise psychology, 109, 138.

Laukka, P., & Quick, L. (2013). Emotional and motivational uses of music in sports and exercise: A

questionnaire study among athletes. Psychology of Music, 41(2), 198-215.

Cumming, J., Olphin, T., & Law, M. (2007). Self-reported psychological states and physiological

responses to different types of motivational general imagery. Journal of Sport and Exercise

Psychology, 29(5), 629-644.

Foster, D. J., Weigand, D. A., & Baines, D. (2006). The effect of removing superstitious behavior

and introducing a pre-performance routine on basketball free-throw performance. Journal of Applied

Sport Psychology, 18(2), 167-171.

Cotterill, S. (2010). Pre-performance routines in sport: Current understanding and future

directions. International review of sport and exercise psychology, 3(2), 132-153.

Will has a Master’s degree in Strength & Conditioning from Middlesex University, and is a published scientific author. Will has worked with athletes across a variety of sports including rugby, football, hockey, cycling, rowing, and recently was the Head of Strength & Conditioning for the inaugural year of the NFL Academy in North London. For more information about Innervate Performance, check out our coaches page

Harriet is a Performance Nutritionist at Loughborough University where she specialises in supporting team-based university, national and international athletes. Harriet has worked within a multitude of sport including hockey, basketball, badminton and cricket. Harriet is a graduate in Sport and Exercise Science (2014) from the University of Leeds and also has a master in Sport and Exercise Nutrition (2016) from Loughborough University

Tulio is a Performance Psychology Consultant at University College London (UCL), and is a UK Representative of the European Network of Young Specialists in Sport Psychology (ENYSSP). He holds a BSc in Sport and Exercise Sciences (Human Performance), and an MSc Sport and Exercise Psychology. Tulio is also a Supervised Sport Scientist (Psychology) with the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences (BASES)