Your Competition Period is the most important time of the sporting calendar. Whether you have a match, race or fight every week, or every month, all of your attention during the competition period must be put towards performing at your best in competition. This means you will be doing lots of tactical, technical and psychological preparation, and might have little time or energy for Strength & Power training. However, abandoning Strength & Conditioning training has been shown to lead to reductions in athletic performance (1), and resistance training has been shown to reduce the risk of injuries in youth and adult athletes (2,3). As such, it is a good idea to continue doing some S&C work, but it needs to be at just the right amount to confer its benefits, and without affecting your ability to compete at your best.

Strength & Conditioning

As with any time of the year, overall workload must be managed to prevent overtraining, injury or mental burnout. While excessive workloads can lead to overtraining, injury and illness (4), inadequate training loads can lead to an athlete being underprepared for the demands of competition, increasing the risk of injury (5). This underpins the need to find a Minimum Effective Dose: the least amount of work you can do to maintain adaptations and reduce injury risk, but not doing so little work that your performance gets worse and you risk injury. There is research examining where that point lies, but ultimately it will need to be tailored for the sport, squad, and individual, just like all other training at every time of the year. To establish a baseline of performance off which you will base all future assessments, you will need a well-established, repeatable physical test that is relevant to your sport, and that doesn’t generate significant fatigue in and of itself (e.g Countermovement Jump height, Broad Jump distance, Drop Jump height & Ground Contact Time, Med Ball Toss distance, 7-stroke RowErg Mean Power, 5-second WattBike Peak Power etc.). You can subsequently use the same test, at a time when you’re not under significant fatigue, to assess whether you’re maintaining/improving your Strength & Power, or if you need to make adjustments to your current plan.

Minimum Effective Dose for Strength

Establishing a Minimum Effective Dose can take some time, but we have some solid guidelines from the scientific literature.

Several studies have shown that 1 Rep Max (1RM) strength can be maintained by performing just one Strength training session per week (6), and while sprint speed can also be maintained with just 1 weekly strength training session per week, one Strength session every 2 weeks is inadequate to maintain 1RM or speed (1). One piece of research lowered athletes’ training from 3 sets, 3 times per week (9 total weekly sets) to just 1 set once per week (1 total weekly set) for 32 weeks and not only did the athletes not get weaker, they actually saw improvements in their 1RM. One commonality in this research is that exercise intensity has remained high with training intensity at 4-12 rep max loads (90% - 70% or 1RM) and training to or close to failure (7).

Minimum Effective Dose for Power

There is less evidence available on the minimum effective dose to maintain power adaptations, however maintaining 1RM strength will go a long way to maintaining power due to the high correlation between the two physical properties (8). Volume for power training should always be kept quite low, as evidence shows that in a given set, power decreases significantly from rep 6 onwards (9). Further, simply competing in your sport, along with regular strength training, will maintain a certain level of power due to the demands of the sport itself.

When should I do Strength Training?

During your competition period, it is imperative that you be as fresh as possible when you compete, so any supplementary training should afford you enough rest before your game/race/event to ensure that the fatigue has dropped by then. While the recommended strength training is very low in volume and frequency, having a day of rest in between S&C training and your event will allow you to fully recover & adapt to the training, while also being at your freshest for gameday.

Nutrition

Maintaining strength throughout a competitive season is important to improve performance and prevent injury. Building and maintaining strength requires having the correct training stimulus and good nutritional strategies to optimise recovery and stimulate muscle adaptations. This article will explore some frequently asked questions about the macronutrient protein, which is essential when it comes to building and maintaining strength.

How much protein should I eat?

While protein is important to help maintain strength, more is not necessarily better! When wanting to maintain strength, aim for about 2g or protein per kilogram of body mass (i.e. 2g/kg). As an example, this would equate to consuming 140g of protein for a 70kg athlete.

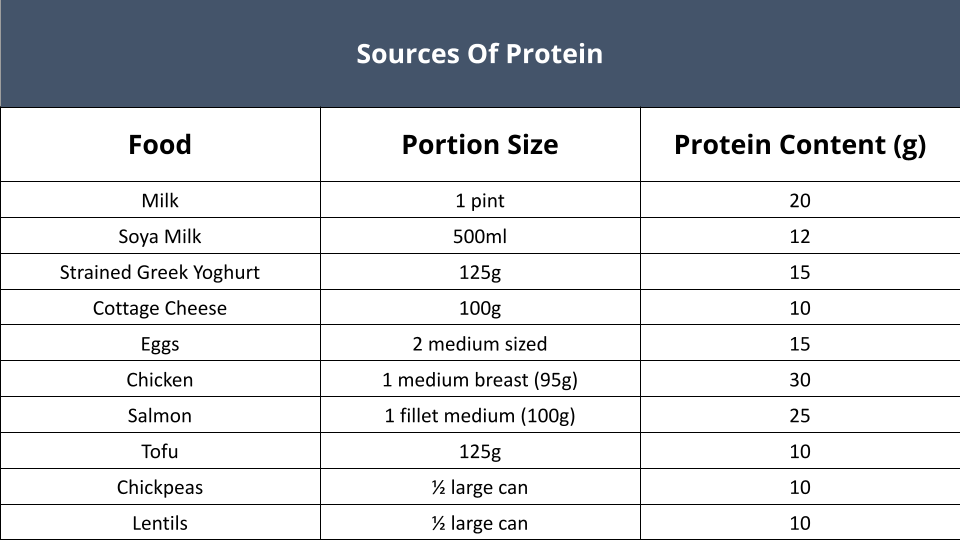

What are good sources of protein?

“Complete” proteins contain all the essential amino acids the body needs to repair and grow and are typically found in animal-based products such as poultry, fish, eggs, and cheese. Plant-based proteins are limited in some essential amino acids and therefore those following this type of diet may just need to plan their protein intake a bit more carefully. In practice, this means consuming a variety of plant-based, protein rich foods throughout the day. Plant-based protein sources include beans, lentils, edamame, and tofu.

How can I get more protein into my diet?

There are some quick and easy ways to increase the protein content of your diet. Firstly, have a source of protein with every meal. This may mean topping your porridge with Greek yoghurt, having eggs for lunch, and eating chicken at dinner. Secondly, try to incorporate some high protein snacks throughout the day such as beef jerky or cottage cheese on rice cakes. Lasty, have a high protein-based snack before bed such as a glass of milk or a bowl of yoghurt.

When is it important to have protein?

Protein intake should be spread throughout the day (every three to four hours), and, most importantly, consumed around resistance exercise.

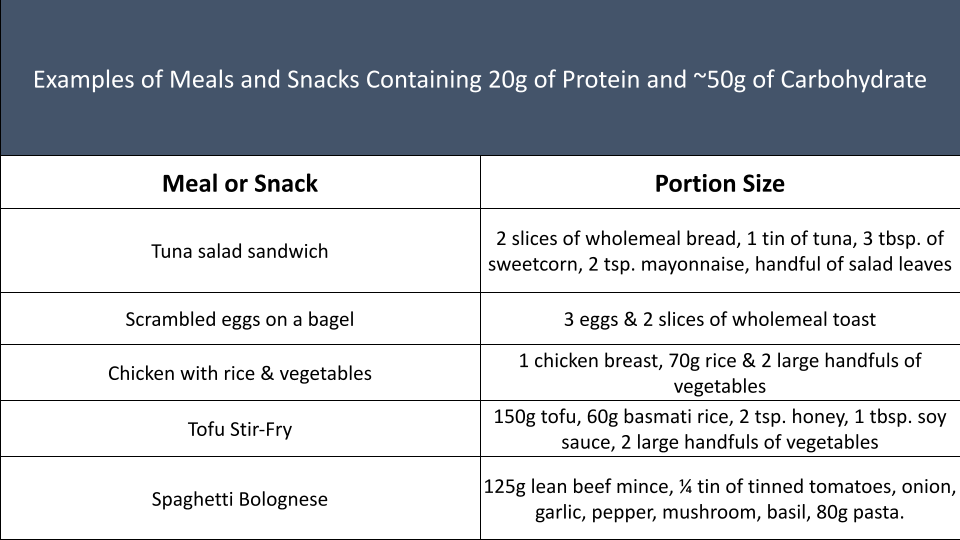

As soon as possible after exercise (or at least within one hour), aim to have a snack or meal containing at least 20-40g of high-quality protein combined with a source of carbohydrate. Not only will this help repair the muscles and support adaptations, but it will also aid in replenishing energy stores. Examples of post-training recovery snacks include sandwiches containing lean meat or tuna, chocolate milk and beef jerky.

In addition, having a source of protein, notably casein, thirty minutes before bed may also be beneficial when it comes to maintaining strength. Casein proteins provide a sustained rate of amino acid absorption over a number of hours and have been shown to be advantageous for muscle protein synthesis and recovery. Examples include the likes of milk, yoghurt and cottage cheese.

Psychology

Your sport and training influence strength and power. How you maximise these outputs is defined by you. A common way to tap into strength, seen in the athletes we work with, is their ability to ‘zone in’ and concentrate fully on their body and how their mind responds to events. Knowing how to summon your strength and power through concentration enables you to work towards what you want to achieve.

Concentration allows you to focus effectively on a task without becoming distracted. Many sports require extended periods of focus, much more than what’s used in an average day. When exploring their best performances, athletes often refer to how much focus they had while executing the task and the deliberate effort they put into it. On competition day, athletes can use concentration techniques to enhance their deliberate effort. These techniques are underpinned by the notion that your body responds according to what your mind is focused on.

The first step to concentrating is knowing what to concentrate on… seems simple, right? You might be surprised (or not) at how often athletes step onto a court, pitch, or ring and are not consciously aware of what to focus on. Of course, the most obvious focus is often on winning or achieving a Personal Best. However, you will need to be more specific to optimise your strength and power. Clarifying and setting performance goals is a great way to start. These goals are specific actions that are within your control. When working with athletes, this narrowing of focus is often referred to as ‘controlling the controllables’. For example, a boxer might want to focus on landing their first two shots with 100 percent accuracy. Take a moment to think of your own performance goal(s) for your next competitive event.

The second step in concentrating is related to our previous blog on ‘How to Perform Your Best on Gameday.’ In the blog, we discuss the benefits of creating a pre-performance routine. A pre-performance routine encourages you to identify your optimal arousal levels, enabling you to harness your strength and power. Importantly, it creates space before your event to consciously choose what to focus on. Check out that post for more details on creating a pre-performance routine.

The final step in concentrating relates to how you speak to yourself and your use of ‘self-talk’. Commonly, athletes engage in self-talk to assess their performance (e.g., “good shot” or “that was terrible”). However, another form of self-talk, known as a cue word, can help athletes focus on their performance goal, ensuring they continue to concentrate throughout the event. For example, a runner might say “drive” when wanting to focus on the power in their legs going uphill or for a sprint finish. This word reminds them of what their mind should be concentrating on at that time. Take a moment to think of a cue word(s) that’s relevant to your performance goal(s). Tip: make sure your cue word refers to the present moment; it should not be future-focused. Using cue words is a technique you will use in the here and now rather than down the line.

Remember, concentration will determine where you direct your power and strength and for how long you can maintain deliberate focus.

Summary

Use a sport-specific physical test battery to evaluate baseline power/speed/strength, use the guidelines above to reduce strength training volume and frequency to a level that should maintain it, re-test the battery after 4-8 weeks to assess how well those physical qualities are being maintained, and adjust from there. Strength can be maintained throughout a competitive season, and both resistance training and a high-protein, good quality diet with regular protein doses throughout the day are essential in order to achieve this. Concentration and focus should be maintained at all times so that you have a clear goal to achieve, which will allow you to best apply your efforts. At Innervate Performance, we will test, train, and monitor your performance to ensure your best performance all season long. Get in touch to find out more at info@innervateperformance.com

Reference

Peterson MD, Alvar BA, Rhea MR. The contribution of maximal force production to explosive movement among young collegiate athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2006 Nov;20(4):867-73. doi: 10.1519/R-18695.1. PMID: 17194245.

Balshaw TG, Massey GJ, Maden-Wilkinson TM, Lanza MB, Folland JP. Neural adaptations after 4 years vs 12 weeks of resistance training vs untrained. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019 Mar;29(3):348-359. doi: 10.1111/sms.13331. Epub 2018 Dec 9. PMID: 30387185.

Brigatto FA, Lima LEM, Germano MD, Aoki MS, Braz TV, Lopes CR. High Resistance-Training Volume Enhances Muscle Thickness in Resistance-Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2022 Jan 1;36(1):22-30. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003413. PMID: 31868813.

Costa BDV, Kassiano W, Nunes JP, Kunevaliki G, Castro-E-Souza P, Rodacki A, Cyrino LT, Cyrino ES, Fortes LS. Does Performing Different Resistance Exercises for the Same Muscle Group Induce Non-homogeneous Hypertrophy? Int J Sports Med. 2021 Jul;42(9):803-811. doi: 10.1055/a-1308-3674. Epub 2021 Jan 13. PMID: 33440446.

Peterson MD, Rhea MR, Alvar BA. Applications of the dose-response for muscular strength development: a review of meta-analytic efficacy and reliability for designing training prescription. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 Nov;19(4):950-8. doi: 10.1519/R-16874.1. PMID: 16287373.

Hazell, J., Cotterill, S. T., & Hill, D. M. (2014). An exploration of pre-performance routines, self- efficacy, anxiety and performance in semi-professional soccer. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(6), 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.888484

Shaw, D. (2002). Confidence and the pre-shot routine in golf: A case study. In I. Cockerill (Ed.), Solutions in sport psychology (pp.108–119).

Mesagno, C., & Mullane-Grant, T. (2010). A comparison of different pre-performance routines as possible choking interventions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(3), 343–360. https://doi. org/10.1080/10413200.2010.491780

Clyde, W., & Serratosa L. 2006. Nutrition on match day. Journal of Sport Sciences. 24(7), pp.687-697.

Hills, S. &Russell, M. 2018. Carbohydrates for soccer: a focus on skilled actions and half-time practices. 10(1) 22.

Holway, F. & Spriet, L. 2011. Sport-specific nutrition: practical strategies for team sports. Journal of Sport Sciences. 29(1). Pp. 115-125.

Harrison PW, James LP, McGuigan MR, Jenkins DG, Kelly VG. Resistance Priming to Enhance Neuromuscular Performance in Sport: Evidence, Potential Mechanisms and Directions for Future Research. Sports Med. 2019 Oct;49(10):1499-1514. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01136-3. PMID: 31203499.

Greenlees, I., Moran, A. P., & British Psychological Society. Sport and Exercise Psychology Section. (2003). Concentration Skills Training in Sport [E-book]. British Psychological Society.

Harle, S.K. & Vickers, J.N. (2001). Training quiet eye improves accuracy in the basketball free throw. The Sport Psychologist, 15, 289–305.

Jackson, R.C. (2001). The pre-shot routine: A pre-requisitie for successful performance? In P.R. Thomas (Ed.), Optimising performance in golf (pp.279–288). Brisbane: Australian Academic Press.

Weinberg, R.S. (2002). Goal-setting in sport and exercise: Research to practice. In J. Van Raalte & B.W. Brewer (Eds.), Exploring sport and exercise psychology (2nd ed.) (pp.25–48). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Will has a Master’s degree in Strength & Conditioning from Middlesex University, and is a published scientific author. Will has worked with athletes across a variety of sports including rugby, football, hockey, cycling, rowing, and recently was the Head of Strength & Conditioning for the inaugural year of the NFL Academy in North London. For more information about Innervate Performance, check out our coaches page

Harriet is a Performance Nutritionist at Loughborough University where she specialises in supporting team-based university, national and international athletes. Harriet has worked within a multitude of sport including hockey, basketball, badminton and cricket. Harriet is a graduate in Sport and Exercise Science (2014) from the University of Leeds and also has a master in Sport and Exercise Nutrition (2016) from Loughborough University

Tulio is a Performance Psychology Consultant at University College London (UCL), and is a UK Representative of the European Network of Young Specialists in Sport Psychology (ENYSSP). He holds a BSc in Sport and Exercise Sciences (Human Performance), and an MSc Sport and Exercise Psychology. Tulio is also a Supervised Sport Scientist (Psychology) with the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences (BASES)